Midway through the journey of our life, I found

myself in a dark wood, for I had strayed

from the straight pathway to this tangled ground.

How hard it is to tell of, overlaid

with harsh and savage growth, so wild and raw

the thought of it still makes me feel afraid.

Death scarce could be more bitter...

Just how I entered there I could not say.1

Midlife is a phase of development as natural as the change of seasons. At this time of life Nature has built into us a drive towards becoming the person we were always meant to be. To this end, we find ourselves longing to lead a more meaningful and soulful life, to find a vocation that speaks to the heart, to complete unfinished business from childhood, re-assess our core values, deepen relationships, and forge a new sense of self.

As this process begins we find ourselves stranded between who we were and who we are to become. We experience angst and confusion as in no other time in our lives. We not only find ourselves in “this tangled ground,” but trying to make our way through it is downright maddening.

Understandable. We have worked so long to know and define who and what we are. Our resistance to being changed is strong. We don’t want to acknowledge or accept that we are in the midst of some kind of un-asked-for inner renovation.

What makes this undertaking even harder is that the people closest to us seldom understand the depths of our suffering. On a collective scale it is poorly understood by our externally focused and wildly extroverted American culture. Since few seem to understand and appreciate the inner fortitude needed to navigate this journey I wanted to share my hit on what happens, why, and where it leads. Make no mistake- this is mighty work. And is best undertaken with a trusted ally, someone who has traveled the paths, and knows the way through.

“Nature seems to have built into organisms an innate

healthy-mindedness; it expresses itself in self-delight,

in the pleasure of unfolding one’s capacity into the world,

in the incorporation of things in that world.”2

It may be helpful to briefly review what we’ve gone through to make it to midlife. Birth to about age 35 is mainly driven by character formation. In childhood our prime instinct is to survive. Nature has installed in us a variety of behaviors to insure that we bond with our caregivers so that we are safe. The degree to which we develop a secure attachment with them is the degree to which we can live with a sense of inner trust. We can then engage with physical world reality full of hope, faith, and competence. And we can bring the same level of self-assurance to our emerging creative life.

Adolescence is a shakier but equally important time for character formation. It brings the sexual drive and puts us in direct contact with our creatureliness as sexual beings (with all of the relational challenges that poses). It also brings intense glimpses into personal potentials, collective idealism, and an instinctive need to belong to a group that shares these ideals. If enough mirroring and social acceptance happens we might get to enjoy a high level of self-esteem (how one feels in relation to others) and self-confidence (how one feels about oneself).

But more than anything, this is a time when profound questions are generated from deep within our hearts, questions that return at midlife. Examples are how am I unique? How do I cultivate this? Give it shape? What gifts do I carry for the world? What should I expect back from it? How can I live into this uniqueness with the full force of my mind, body, heart and soul? How might it bring meaning both to my life and to those around me?

In adulthood these adolescent potentialities and dreams can get buried beneath wider collective social demands. We get swept up in running with the herd- pulling one’s weight in the world through a career, the starting of a shared life that may include marriage, children, preschools, PTA meetings, managing in-laws, owning property, saving for the future.

So the overall work of the first half of life is developing a strong ego, built from the feedback we get from those around us in response to everything we do. If all goes well, and often it does not, we develop confidence in knowing we are lovable, capable, grounded in reality, can trust others, and that our self-definitions are clear and firm.

“When the world defeats the ego, the soul can float;

then fantasy and imagination…have a chance

to enter the scene and be noticed.”3

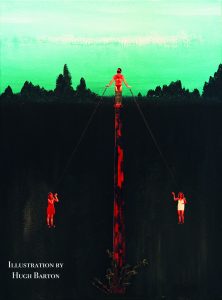

But somewhere between ages 35 and 50 this begins to change. There is a feeling of losing our way, being unmoored from reality, of questioning our sense of self. The “self-delight” of engaging with the outer world loses its charm. The life force, once directed outward, introverts. I like to use the analogy of the tides. In the first half of life we are like the ocean wave that enjoys the sheer energy it contains to surge forward, scooping up everything it encounters and incorporating it. In midlife the wave has landed ashore, but before it returns to its own depths there is a period of inertia- a slack tide. The midlife space in which we find ourselves feels like slack tide, like one is living in limbo. Floating. Directionless.

This floating feeling is extremely unsettling. As Murray Stein writes, “a person seems to stand perpetually at some inner crossroads, confused and torn.”4 In my clinical work, as well as my own midlife crossing, new types of thoughts and emotions arise at this time. They can signal the start of the midlife transformational process. Some are on the manic side; unpredictable moodiness, impulsivity, new and unusual sexual energy and fantasies, a myopic focus on a hobby, out-of-the blue fits of anger or frustration, and a susceptibility to critical comments by others that leads to self-doubt. Some are on the depressive side; a sense of being disconnected from other people, a lack of energy, overwhelm with simple everyday tasks, sadness at the loss of youthful physical vitality, hopelessness that leads to a desire to isolate oneself, thoughts of being a fraud, confusion about your role in relationships, loss of understanding the nuances in social situations, boredom, and dullness of thought.

This experiential intensity shakes us up. We start to realize that something inside is different, more problematic. Questions get generated similar to those in adolescence. Who am I really? Why am I here? “What is my true calling? Where is my true Self? What is happening to me?” (“This is not my beautiful house/This is not my beautiful wife”5 ).

To be clear- by “I” and “me” I mean ego- the conscious personality, built up, bit by bit, by the thoughts we think, the emotions we feel, the sensations we endure, the possibilities we intuit, and the memories we store. By Self I mean the as-yet-to-be-discovered center of an unlimited and indefinable total psychic reality, or soul, which contains the ego.

“Without noticing it, the conscious personality is pushed

about like a figure on a chessboard by an invisible player.

It is this player who decides the game of fate,

not the conscious mind and its plans.”6

As this process unfolds the Self throws up forces within the personality that work in opposing directions at the same time. One direction is regressive and works to resolve first-half-of-life issues; to “work-through” some of the tasks that were left unfinished. The trick here is to do it consciously. As James Hollis writes, “those who travel the passage consciously render their lives more meaningful.”7

We can tell that regression is happening when we notice things like a heightened need to be felt, seen, and heard by another- to be nurtured in ways our mothers never could. Other experiences may include being driven to take up activities we did when we were teenagers, sexual fantasies involving older people, an emotional tug at the heart to re-connect with family and friends, and jumping into new activities that promise excitement without stopping to consider the consequences. We may also experience new kinds of dreams. These can include being physically held or supported by an older/wiser person, images of token animals, or a return to our childhood home.

The developmental tasks calling to be worked through can include wanting to feel securely attached to another, developing better boundaries with others, resolving narcissistic wounds, and finding peace from early traumas. It is a great time to gain insight into the defenses we use to keep us from living honestly and courageously. This last one is vital yet tricky, since defense mechanisms, like denial, repression, etc., are unconscious. Therapists can be valuable allies for this work.

The other direction is progressive and works to connect us with a new form of life-giving energy that is not generated by the conscious personality. It starts as a tiny glimmer of something unnamed in our heart, as a twinge of intuition about something transpersonal awakening inside of us. If we are able to bring awareness to these dim experiences then we begin to have a sense of something soulful arising. C.G. Jung used the term religio to signify this natural movement of the Soul to re-inspect one’s life and connect with a richer and expansive transpersonal experience.

We can tell that this progression is happening when we start to notice a sense of being connected to something bigger than oneself, a new curiosity about a religion or spiritual practice, a novel feeling of kinship with many people and greater tolerance for any differences, paring down the focus of work, interests, and hobbies to things that feel meaningful. We may take less interest in other people’s views because we are working on nurturing our own. We also have thoughts that the talents we possess were not made by us but have been given to us; we find ourselves saying “I don’t know” more often; dreams emerge with themes of ancient civilizations, figures of the gender opposite our own, scenes of expansive vistas/horizons, religious imagery, and many more. Therapists trained in the Analytic (Jungian) tradition can be extremely valuable allies in helping to facilitate the budding Ego/Self relationship.

“Man will be forced to develop his feminine side,

to open his eyes to the psyche and to Eros.

It is a task he cannot avoid.”8

Men seem to suffer at midlife more acutely than women. Because, in general, they are less attuned to their inner world. Men are less discerning about their feelings and emotions. In addition, they tend to suffer this midlife change in isolation, which makes things even harder for them. Women seem to be much better at feeling connected to their inner processes as they happen in real time, and are more apt to reach out to others. Many women live fundamentally from a place of Eros (the ability to share empathic attunement and physical relatedness), something men are in need of learning.

What Nature seems to provide at midlife is the opportunity to balance out the personality. We develop inner qualities that were not central to the developmental needs in the first half of life. For men these are new “feminine” qualities, including empathy, humility, compassion, relatedness (as Eros), caring, patience, balance, and sincerity.

For women experiencing midlife woes, cultivating Eros seems to focus on social differentiation. This may include making boundaries with others (so that a clearly defined and independent “I” is relating with others on equal terms), redefining the relationship with one’s parents, children, or mate, an interest in belonging to a women’s group, renewed attention on physical health, and an attraction toward mastering a meaningful new vocation, skill, talent, or cause.

“The telling question of a person’s life is their relationship to the infinite.”9

So where is all this leading? The genuine work of midlife is more than re-balancing the personality, more than getting comfortable with the floating. It is noticing that our sense of self is changing profoundly. The vital lie of the character we erected in the first half of life becomes threadbare, and through the holes we get glimpses of a transcendent presence within.10

Here is the inner gold we have been struggling to find in the course of the midlife journey. We begin to notice a new inner light. It carries new knowledge and an unshakable sense of self that is bigger than the narrow confines of the ego. We soon discover that this new experience is self-shining, spontaneously present, deeply soulful.

Awareness of this inner presence allows us to witness all the thoughts, emotions, and somatic experiences as they arise without being blindsided by them or giving in to them and acting out. By tasting this new soul-filled center we start to feel connected to all beings, and our relationships begin taking on compassion and love. It is from this place that we find answers to our most important fundamental questions. If we know how to listen.

Over time what emerges is the capacity to better host ambiguity, paradox, and mystery in Nature, in others, and most importantly, in ourselves. We develop patience with not knowing. We become better attuned to inner experiences, including our ever-changing moods, thoughts, sensations, perceptions, and intuitions. With enough conscious attention to the struggles of midlife we arrive at the Self- the limitless center to which we experience an effortless union and from which we derive new personal meanings.

References

1Alighieri, D. (2002). Inferno (M. Palma, Trans.) New York, NY: Norton

2Becker, E. (1973). The Denial Of Death. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster

3Stein, M. (1983). In Midlife. Putnam, CT: Spring Publications

4Ibid.

5Byrne, D. et al. (1983). Burning Down The House (Recorded by Talking Heads). On Speaking In Tongues. New York, NY: Sire

6Jung, C. G. (1966). The persona as a segment of the collective psyche. In H. Read et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.) (Vol. 7, p. 161). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

7Hollis, J. (1993). The Middle Passage. Toronto, Canada: University Of Toronto Press

8Jung, C. G. (1964). Women in Europe. In H. Read et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.) (Vol. 10, p. 125). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

9Jung, C.G. (1933) Modern man in search of a soul. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin

10Becker, The Denial of Death