It is one thing to hear a goddess’ song from a safe distance the way Odysseus did in the story of the Sirens. But actually wrestling with a god is another matter altogether.

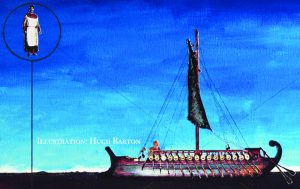

In this story it isn’t Odysseus who wrestles the sea god Proteus. It’s one of Odysseus’ fellow generals in the Trojan war- Menelaus. Towards the beginning of the poem Odysseus’ son, Telemachus, has left home to seek news about his missing father. On his journey he visits Menelaus and Helen (the very same Helen who “launched a thousand ships” and caused the Trojan war). Menelaus doesn’t have any recent news, only what Proteus told him ten years earlier when he left Egypt- that Odysseus was alive but being held captive by Calypso with no hope of return. And it is Menelaus who proceeds to tell this myth;

When Dawn spread out her fingertips of rose

I started, by the sea’s wide level ways,

Praying the gods for help, and took along

Three lads I counted on in any fight.

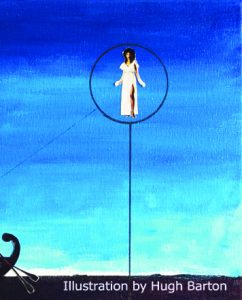

Meanwhile the neriad Eidothea swam from the lap of Ocean

Laden with four sealskins, new flayed

For the hoax she thought of playing on her father Proteus.

In the sand she scooped out hollows for our bodies

And sat down, waiting. We came close to touch her,

And, bedding us, she threw the sealskins over us-

A strong disguise; oh, yes, terribly strong

As I recall the stench of those damned seals.

Would any man lie snug with a sea monster?

But here the nymph, again, came to our rescue,

Dabbing ambrosia under each man’s nose-

A perfume drowning out the bestial odor.

So there we lay with beating hearts all morning

While seals came shoreward out of ripples, jostling

To take their places, flopping in the sand.

At noon the ancient issued from the sea

And held inspection, counting off the sea-beasts.

We were the first he numbered: he went by,

Detecting nothing. When at last he slept

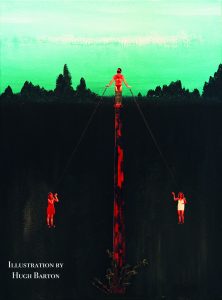

We gave a battlecry and plunged for him,

Locking our hands behind him. But the old one’s

Tricks were not knocked out of him; far from it.

First he took on a whiskered lion’s shape,

A serpent then; a leopard; a great boar;

Then sousing water; then a tall green tree.

Still we hung on, by hook or crook, through everything.

Until the Ancient saw defeat, and grimly

Opened his lips to ask me:

“Son of Atreus,

Who counseled you to this? A god: what god?

Set a trap for me, overpower me- why?”

He bit it off then, and I answered:

“Old one, you know the reason- why feign not to know?

High and dry so long upon this island

I’m at my wits’ end, and my heart is sore.

You gods know everything: now you can tell me:

Which of the immortals chained me here?

And how will I get home on the fish-cold sea?”

He made reply at once:

“You should have paid

Honor to Zeus and the other gods, performing

A proper sacrifice before embarking:

That was your short way home on the winedark sea.

You may not see your friends again, your own fine house,

Or enter your own land again,

Unless you first remount the Nile in flood

And pay your hecatomb to the gods of heaven.

Then, and then only,

The gods will grant you the passage you desire.”

One of the things about this myth that is so striking to me is the courage and commitment of Menelaus and the “three lads.” As I view this story as a personal dream then I am all four of these men, and each one plays a different part.

The number four has been associated with modes of consciousness for centuries. In the ancient Greek tradition there are the four Elements- Earth, Air, Fire, and Water (plus a fifth that is sometimes included- Space). At the time of Homer these elements were associated more with physical world reality than with psychological realities. But they did discuss the human character in terms of elemental polarities. Typically they defined one extreme pole as Love and the other, Strife, and there was the recognition of the grey areas in between.

One early Greek philosopher, Empedocles, associated these elemental polarities with a god. Zeus, as the element Air, possesses a character that includes perseverance, inflexibility, realism and pragmatism. The goddess Persephone, associated with Water, spring, and innocence, characterizes a personality that is open and flexible, oriented toward harmony and nurturance. To be like the Earth goddess Hera meant you were prone to stormy rage and jealousy, but also supportive of new life. And if you possess qualities such as intuition, creativity, and self-sufficiency and stillness, you might be associated with Fire and with Hades.

In Buddhism the four elements, known as the Four Noble Truths, are a basis for understanding suffering and for liberating oneself from it. These are 1) To be alive is to suffer, 2) The cause of suffering is attachment to transient things, 3) We can end this suffering through renunciation, 4) There are teachings that enable us to abide as the unchanging essence of what we truly are.

In modern terms we now associate the four ego faculties through C.G. Jung’s definitions- Thinking, Feeling, Sensation, and Intuition. The fifth element, in most traditions called Space, falls outside of ego’s domain. It is the space in which all appearances and possibilities can arise, including man and his localized human experiencing

Jung divided the four ego functions further into the polarities of introversion (directing one’s attention inward toward thoughts, feelings and awareness- Hera and Hades) and extroversion (directing one’s energy outward toward people, actions and external objects- Zeus and Persephone.) When the opposing elements of the ego encounter each other, they might neutralize each other, or they might lead to integration and a deeper sense of Loving and of peace. In this myth Menelaus and his three comrades prevail over Proteus, indicating that the four functions have been integrated and a deeper level of knowing and loving has occurred.

The harmony between Menelaus and his crew mates to subdue Proteus is a beautiful symbol for how to deal with any dilemma.

We can deal with our own inner dilemmas by considering four principles. These are Intention, Surrender, Acceptance, and Forgiveness.

Intention

Throughout The Odyssey the characters ask for what they want. They are very honest and explicit with their requests, whether to the gods, the ogres, or to their fellow man. Having clarity about what we want allows us to work with the energy of the universe. Although this might sound to many as “new-age-y” this is exactly what the characters in The Odyssey do. When requests are made, say, of the gods, these “prayers,” these intentions, are answered. I think it’s Homer’s recognition that our intentions have a power that can manifest what it is for our highest good.

In this myth, Menelaus and the goddess Eidothea work together, and they have three clear intentions. The first is to hang on no matter what happens. As Homer wrote, “we gave a battle cry and plunged for him, locking our hands behind him. But the old one’s tricks were not knocked out of him; far from it. First he took on a whiskered lion’s shape, a serpent then; a leopard; a great boar; then sousing water; then a tall green tree. Still we hung on, by hook or crook, through everything. Until the Ancient saw defeat”. The second is to ask why they have been detained. And the third is to request safe passage home. As we know from the story, all three intentions manifest.

Surrender

When specific intentions are voiced in The Odyssey the results are left up to the individual god or man. The “requestor” stays out of the results. It is a tremendous thing to be able to do. How many of us spend our lives working feverishly to control the results in a desired situation? Most of us do this to a great expense to our relationships. We focus on the details of things and we fail to recognize that we never really do anything alone. If I assert that I alone created the illustrations for this book it’s simply not true. Did I make the brushes I used? The canvass? The paint? Did I make the camera that photographed the canvasses? Did I create the light that let me see it all? Did I build the computer on which I manipulated the images? The list can go on and on. I had hundreds, maybe thousands, of fellow human beings helping me to create this little book. I think the ancients, including Homer, understood the holographic nature of reality, and that Intention and Surrender were tools of humility to help us understand our place within creation.

Acceptance

Menelaus and the men demonstrate another characteristic of a psyche that is integrated- they can accept what is. In order to accept what is we need be free of judgments- of ourselves and of others. For as soon as we judge something we fall into the subtle trap of turning our direct experience of what is into a concept. And the concept, our idea of something, is never the thing itself. It’s like mistaking the map for the territory. An example of how this would work in this story might go something like this. When Menelaus sees Proteus for the first time he could think, “He looks a lot like my father.” This judgment might then proceed along these lines; “Proteus looks like my father, my father used to beat me, I had no power with my father, I’ll have no power with Proteus, I’m going to lose here once again, I’m going back to the ship.”

There is a long list of things that need to be accepted for Menelaus’ intentions to succeed; he must accept his own fear as it arises, he must accept the words of the goddess, he must trust and accept that the other men will not lose heart and let go; he must accept he won’t be eaten by the lion, or drowned by the water, or bitten by the snake, or gored by the boar, or mauled by the leopard, or plunge to death falling from the tree’s height; he must accept that Proteus will give him correct answers to his questions. By accepting what is he is able to honor his ultimate goal- to return home. As we’ve seen in other parts of this book, a return home means recognizing in ourselves the wholeness, integration, and loving that is our natural state.

Forgiveness

Of the four traits Forgiveness may be the most important. While Intention, Surrender, and Acceptance are ways to control our personal inner state, Forgiveness is a recognition that we are in relationship. One characteristic of being in relationship is that we acknowledge our own pain as well as the pain of others. This shared experience, this shared suffering, we call compassion. I think that the reason Menelaus ultimately succeeds in subduing Proteus is not because he has a clear intention, or can surrender to the powers, or can accept what is, but because all three of these things occur while he is sharing the experience with the three lads he “counts on in any fight.” It’s the interpersonal bridge between the four men that ultimately leads to success. When the four aspects of our personality are in harmony, when we experience mastery over them, when they can work as a team, then and only then can we move away from our ego’s narrow definitions of self. When we achieve a high level of integration and psychic harmony we are free to explore what we may be. If we utilize these four skills when our own dilemma arises we may be able to conquer any issue that causes suffering.

Proteus The Shapeshifter

One of our greatest psychological challenges is to know what we are when we’re not thinking about ourselves. For most Westerners we define ourselves by what we think we are. But what are we between thoughts? Can we set aside all thoughts about ourselves and experience directly that aspect of our being that transcends thought? And is it really transcendence or is it simply our naturally free, unobscured condition?

If we continue with the premise that we are all characters in The Odyssey then we are also Proteus. The mythical Proteus is the son of Poseidon and is the herdsmen of seals. He knows the future but will change shape in order to avoid sharing this knowledge with mortals. He will only divulge answers to what he is asked by a person that can contain him. Because of his relationship to the sea, Proteus can be seen to represent our unconscious and the creative energy of the world. To overcome Proteus is to awaken to the recognition that we are the ocean with its potentiality for both wisdom and creativity. So in grappling with Proteus we are working to see beyond the small-minded illusions by which we have been defining ourselves and connect to something transcendent. And his shifting shapes are not “out there” but our own condition changing as we grapple with what we truly are.

One way to consider this part of the myth is to view the shapeshifting as our ego’s strategy to keep us under the control it believes it has. Because before and after the struggle Proteus is just what he is. The wish to contain him and to learn his heart knowledge is what starts the scuffle. As Jung writes,

“If a modern individual for whom god is dead, descends into the darkness of the unconscious, and endures its suffering, allows himself to be guided by the spirit of nature, and accepts the shadow, he may experience a whole new life and be redeemed for his crime through the conscious attitude…a new side of the personality will emerge that has to do with the heart…”

The Forms Proteus Assumes

If we consider each of the forms Proteus changes into we can begin to appreciate some of the challenges we will encounter along the way towards wholeness and integration. As such, the shapes that Proteus assumes are meant as instruction, not as punishment. If Menelaus and his men can hold fast to each of the forms that Proteus becomes, then they will be incorporating the characteristics of each into their experience; they will be expanded and imbued with the characteristics of each form. I think that Homer’s message here is that adopting a learning orientation towards life is the correct view, and by doing this, events that appear to be frightening and negative might be reframed as an opportunity for our expansion and upliftment; the scary encounter becomes the great teacher.

From the psychological point of view each of the forms that Proteus takes is a condition already present somewhere within our psyches. Since Menelaus and his men have to hold on “by hook and by crook” we might consider that the forms are not in direct consciousness, but instead reside within the unconscious archetypal realm.

In the world of dreams the lion could represent the part of our Self that is fierce, wild, and untamable by our cultured personas. It exists outside of our learned behaviors and self-limiting beliefs. To encounter our inner lion is to be in the presence of our own capacity for fierceness. In waking life, in consciousness, we are likely to attempt to hide this aspect of our being. In dreams we are free to explore it.

Lions are never cruel- their actions are purposeful and swift. They act with clarity and immediacy, whether they are hunting, mating, or protecting their pride and territory. Homer doesn’t distinguish male from female lion, but it might be useful here to assume that Menelaus and his men encounter both aspects. The female lioness gives birth, raises the cubs, and hunts for the pride’s food. She is the nurturing aspect, especially of the young. The male lion’s role is as sperm donor and protector. He is the guard of discipline and the preserver of order. To meet the lion within is to bring into consciousness our capacity to live with clarity, fierceness, and purpose.

There are many interpretations for what a Serpent represents, and they carry a great variety of meanings depending on the culture. I will focus on what the snake might mean in The Odyssey and in the world of dreams in the context stated above- as instruction on aspects of the psyche. One major characteristic of snakes is that they shed their skin. This happens seasonally, so we could say that Proteus as the Serpent represents rejuvenation and eternal life. He is pointing to this quality of being within Menelaus and his men. I think the implication here is that wisdom, and even transcendent knowledge, already resides within each of them, and that to grapple with the form of the snake is to awaken to our own self-shining, ever-fresh, timeless awareness.

The leopard’s success in the wild is due in part to its adaptability to habitats, its gourmand diet, its ability to sprint at great speeds, its unequaled ability to climb trees even when carrying a heavy carcass, and its well-known capacity for stealth. In context of our inner lives, to be leopard-like is to be flexible and to know how to adapt when different internal states arise.

Wild boars are primarily nocturnal animals. They find food by rooting through dirt, and eat mainly roots and tubers, although they are know to eat eggs, reptiles, and other small animals. They have exceptional hearing and sense of smell, but poor eyesight. They are very vocal and communicate with others through a series of grunts and squeals. Above all else, they are revered as noble and dangerous prey, especially when cornered. I think that in terms the inner life, Proteus is pointing Menelaus and his men to that part of themselves that is comfortable in the dark, in the shadow self. To root around in the dark is a metaphor for that part of ourselves that is willing to investigate the hidden and disowned parts of our being in order to bring them into the light of day- our consciousness.

Water and The Seals

From the psychological standpoint, water has many interesting and important characteristics that help us understand our own process.

A common aspect is that of representing the unconscious. In The Odyssey water, in the form of Ocean, has many names, and as we have already explored, is the prima materia upon which our conscious life floats.

Another important characteristic of water is its adaptability. It flows along paths of least resistance. It runs freely and embraces everything it encounters with the same respect, whether it comes upon a battle ship or a bolder. To be able to hold onto “sousing water” implies that we possess an innate ability to flow and adapt to change- both internally (in the form of self-definitions) and externally (in physical world reality.)

And still another aspect of water is its prevalence in all that lives. Our planet and our bodies are composed mainly of water. It is implicit to life and is the Element most closely associated with the Proteus myth. Proteus lives in the water, as do the seals.

Seals live on both land and sea. The implication here is that they can travel through polarities- from the dark depths of the unconsciousness to the familiar light of our conscious lives. Like the water in which they live they can flow freely from love to strife. When Eidothea dives into the sea and returns with sealskins for Menelaus and his men, she is transferring this quality of marine mammal adaptability to them. They then take this quality into their encounter with Proteus.

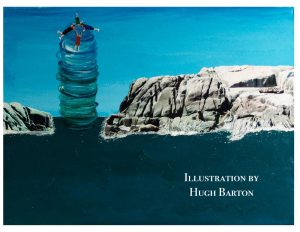

A Tree

A tree is a most marvelous thing and great symbol of completion. Perhaps this is the reason that Proteus’ last transformation is into a tree. Trees have their roots in the dirt, gaining nurturance from the water and minerals in the dark soil. They are topped with leaves that absorb carbon dioxide and sunlight, create chlorophyll, provide shade, and exude life-giving oxygen. They have bark that provides protection for a delivery system between roots and leaves, and limbs that enable birds and other animals to live and thrive.

When Menelaus and his men hold onto the tree I think it’s not from fear of falling but from the sheer joy of touching a localized incarnation of the totality.